“You look Panamanian.”

No three words have ever brought me such joy. I can’t explain why but whenever someone would make this comment to me, even after six months abroad, I still found a tension I didn’t know I was carrying being released from my shoulders and a smile covering my face.

I’ve traveled extensively and in each place my identity has changed with it. In India, I was called African, yet in Cameroon (West Africa), I was called mixed (white and Black). In Brazil, I was Brazilian, assuming I didn’t speak. Here in the US, people often assume I’m African American. The underlying assumption being, I recognize something in you but it’s not from here.

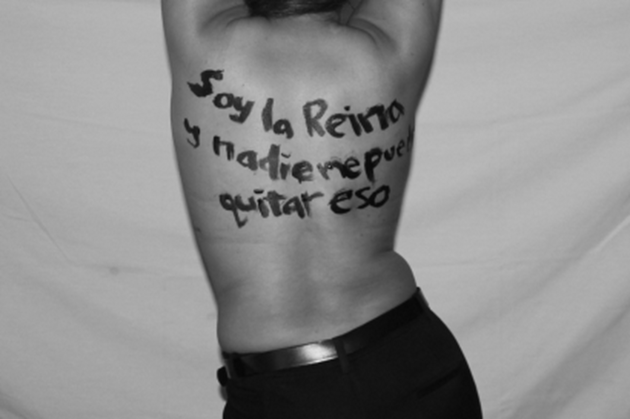

People making assumptions about race and nationality has always been one of my biggest pet peeves. Yet for some reason, anytime I heard, “You look Panamanian,” or “It’s because she’s Latina…,” I found myself feeling reassured. It’s a validation I shouldn’t need but one I think I’ve been searching for all along.

My family is from Panama yet I did not grow up speaking Spanish. This was always a goal of mine. One I tried to accomplish many times to no avail. So, finally, I booked a one way ticket to Costa Rica and Panama, enrolled in language classes and said I couldn’t come back until I was fluent. I’m happy to announce that I have since made it back.

It didn’t hit me all at once but I came to realize that my pursuit for fluency was partially a way to validate my identity. I often felt like I had to overcompensate because when you think of what a Latina looks and sounds like you don’t think of a Brown-skinned, English speaker.

“No, my parents are Panamanian,” I would explain to others. Only to be met with an incredulous face.

“What?”

“But how?”

“So, you’re mixed then?”

“Do they speak English there?”

“Why is your last name Henry?”

At times these questions also came from other Latinas and it would quickly get tiring having to re-explain hundreds of years of history. Fighting ignorance sometimes felt like a full-time job.

Just imagine my happiness when I found myself living for five months as just another face in the crowd, paying resident price for museum admissions, getting asked for directions and basking in the diversity that is the Latino culture.

Just imagine my happiness when I found myself living for five months as just another face in the crowd, paying resident price for museum admissions, getting asked for directions and basking in the diversity that is the Latino culture.

Imagine how weird it was to think that in this space, to be with a white person (even if they were also Latina) was a disadvantage because it meant more expensive taxi rides and being hassled by street peddlers. How weird it was for someone to, by default, ask, “Does she speak English?”

Imagine how awesome it was to see things that only ever happened in my house, or with family friends, happen on a national scale, like a bus full of people making the sign of the cross as they passed a church or eating patacones (tostones) and carimañola for breakfast. I constantly thought I heard relatives’ voices because while their accent is distinct in the US, it’s everywhere in Panama.

Finally, I felt a part of a community where I didn’t have to explain myself. “You look Panamanian.” No question mark.

“Why yes, you’re right, I do.”